From ramps outside buildings, to the small textured bumps at the start of crosswalks, to sign language interpreters at big events — most people have probably seen the effects of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) without even fully registering them.

But until 35 years ago, when the ADA was signed into law, these accessibility features weren’t a given.

The ADA prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability and grants the right to reasonable accommodations. While these might seem like pretty basic civil rights, it took years to actually get them — and much of the fight is steeped in local D.C. history.

“All of this has led to a cultural shift,” Brendan Stern, a Gallaudet University professor and the executive director of the Center for Democracy in Deaf America, told News4 through an American Sign Language interpreter. “Accessibility is now a public expectation, not a private act of charity.”

What is the Americans with Disabilities Act?

The ADA has two main functions.

One is prohibiting discrimination on the basis of disability. This not only applies to people who have a disability, but also those who are perceived to be disabled or are associated with a disabled person.

“You’re not supposed to be able to be fired if, for instance, your employer finds out that you have a child who has a developmental disability, or that you are married to a spouse who has a psychiatric disability,” said Ly Xīnzhèn Zhǎngsūn Brown, a professor at Georgetown University and a disability and legal scholar. “You’re not supposed to be denied access to renting a unit in a building that you otherwise would have qualified for as a tenant because the landlord finds out that you use a wheelchair or you have a service animal.”

“The ADA allows us to be citizens, not burdens. It allows us to be contributing members of this country and its communities, not merely visitors.”

Brendan Stern, Gallaudet University

The ADA’s other function is granting the right to reasonable accommodations.

“In our society, whether how we build buildings, how we run programs, how we interact with people, how we teach, how we work, that all people’s brains and bodies more or less function the same way, look the same and will be the same from the time they’re born to the time they die, we miss so much opportunity,” Zhǎngsūn Brown said. “We design only for one small subset of humans, and in doing so, we end up inadvertently excluding everybody else.”

Stern said his parents, who are also Deaf, had limited options for graduate school before the ADA because only a few universities provided signing in classrooms back then. By the time Stern was ready, though, he had many more choices, because the ADA requires access to sign language interpreters.

“The ADA allows us to be citizens, not burdens,” he said. “It allows us to be contributing members of this country and its communities, not merely visitors.”

While the ADA was a monumental step, advocates say there’s still a long way to go, especially since the main way the ADA is enforced is through lawsuits. Those aren’t feasible for a lot of people with disabilities.

“Someone who is low income or even middle income just may not have the resources, one, to know to hire a lawyer, two, to know what kind of lawyer to hire, or three, to pursue a case through to its natural conclusion,” Zhǎngsūn Brown said. “And that can be very detrimental to disabled people who, for just financial reasons alone, can’t necessarily access the court system.”

And when it comes to reasonable accommodations, it is typically up to private businesses to foot the bill.

“Companies aren’t always willing to pay for interpreters or shoulder the financial burden of hiring Deaf employees — even when those employees are fully qualified and ready to serve,” Stern said.

A long fight

The ADA did not come to be overnight.

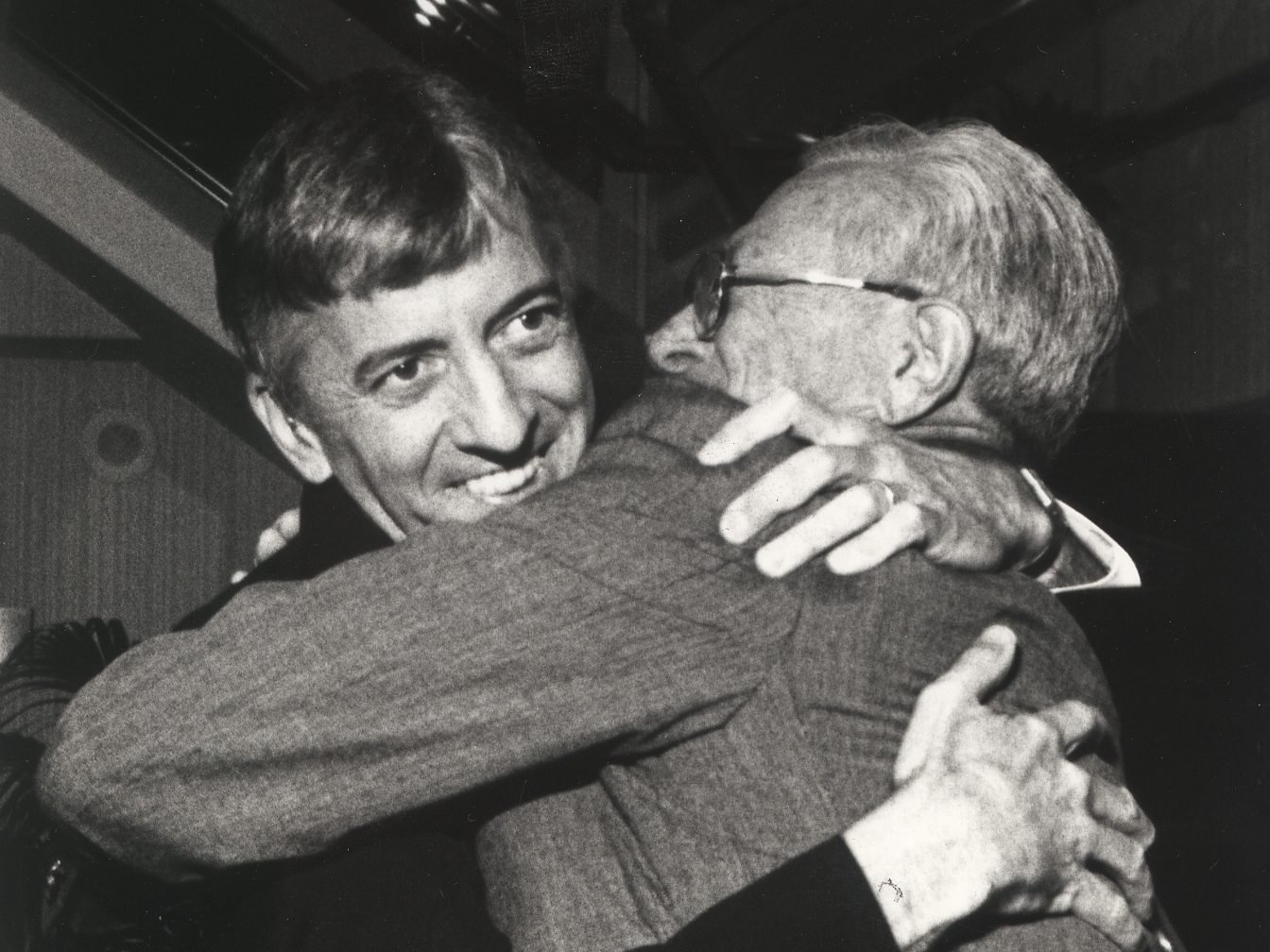

One of its sponsors, Sen. Tom Harkin of Iowa, had a Deaf brother and said the ADA was made possible, in part, because of Deaf President Now, a 1988 movement when students at Gallaudet University in D.C., the first university for Deaf and hard of hearing students, successfully demanded the school hire its first Deaf president.

“This movement showed that we would no longer accept paternalism. Its success led the general public to see Deaf people as capable and deserving of full rights and opportunities,” Stern said. “That same movement led to I. King Jordan’s selection as [Gallaudet] president, proving that Deaf people deserve to lead and belong as full participants in American public life.”

But even once the ADA was introduced in Congress, it still faced hurdles.

Zhǎngsūn Brown explained how there was contention over whether the ADA should include protection for people with mental disabilities or just physical disabilities. Some lawmakers were concerned that because some mental disabilities are less visible, people would try to fake being disabled.

Some more conservative lawmakers thought if mental disabilities were included, members of the LGBTQ+ community would use it to claim discrimination and gain protection. As a result, there is an exclusionary provision in the ADA that names specific groups of people or conditions that categorically could not be covered by its protections.

“The LGBTQ community has rightly named exactly how stigmatizing it is that to be homosexual or transgender is named within this exclusionary provision of the ADA alongside conditions like pyromania and pedophilia,” Zhǎngsūn Brown said. “At the same time, the LGBTQIA movement, at the time of the ADA’s passage, largely applauded this exclusionary provision because they saw it as another way to avoid having queer and trans people lumped into the category of disability.”

The ADA also stalled in the Committee on Public Works and Transportation because of transportation industry objections.

So, on March 12, 1990, disabled activists left behind their mobility aids and crawled up the steps to the Capitol, demonstrating the lack of accessibility in public spaces and forcing politicians to see them. It became known as the Capitol Crawl.

“Looking back to the 1970s — you can look further than that — disabled people have always been resisting from bed, from inside institution walls, in all the places where disabled people have found each other, and all the places where disabled people have been and where we are now,” Zhǎngsūn Brown said.

The ADA was finally passed and then signed into law by then-President George H.W. Bush on July 26, 1990. And since 2015, July has been recognized as Disability Pride Month in commemoration of the anniversary.

What’s next?

The fight for equal access is far from over, advocates say.

A major focus for the present-day disability rights movement is fighting to preserve Medicaid, which is facing major cuts under the Trump administration.

“Particularly for home- and community-based services, to keep disabled people alive, enable disabled people to stay in their own homes, participate in the community, have a social life, have a spiritual life, have an economic life, have a political life, like all the things that we think of as living and living in communities,” Zhǎngsūn Brown said.

Stern noted how fostering civic engagement can help carry on the legacy of the disability rights movement.

“I think the disability rights fight is one that all Americans need to carry forward. It’s about defending public spaces where we can sign freely, disagree openly, and contribute meaningfully to civic life,” he said. “We want to tell stories that offer compelling counternarratives. That, I believe, is the legacy of the disability movement — and it’s the kind of messy work of citizenship we must continue to inspire.”

from Local – NBC4 Washington https://ift.tt/DhTctmF

0 Comments